Philosophy in Physics

Published:

I recently asked my particle physics professor a question that I feel he really disliked. I wasn’t necessarily trying to poke him (but I had a hunch this question would), but at this point in my career, I am trying to absorb every ounce of knowledge and opinion out of the professors I interact with. Because now, it’s not sufficient to just know physics (that might be an oxymoron). I need to start forming educated and defensible opinions on the modern state of physics.

“Is there an anthropic bound on the mass of the Higgs (boson)?”

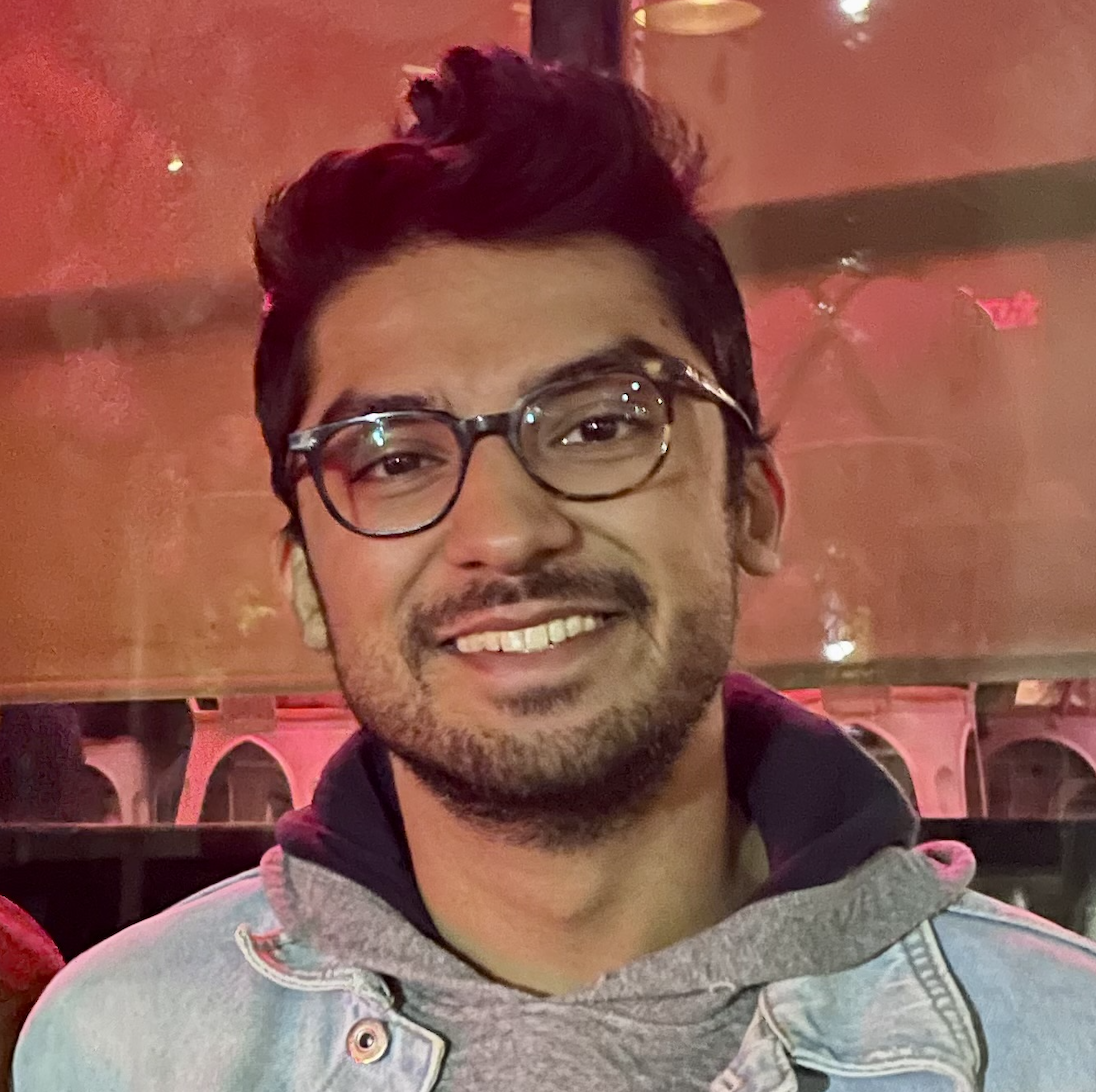

There are a few moving parts here. The Higgs boson is – in the language of physics – a spin 0, massive scalar boson that couples to mass. Its discovery in 2012 at the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland is up to this point the most important scientific discovery in our lifetimes. It’s a profoundly necessary piece of The Standard Model, the most successful and remarkable composition of physical laws ever synthesized. In the Standard Model, the coupling of the Higgs is responsible for giving other particles their mass. The Higgs particle itself is just a manifestation of a much more fundamental object, the Higgs Field and what’s known as the Higgs mechanism. When we get into the nitty gritty of particle physics, describing matter as fields is a much more natural and appropriate description. Sorry.

This is *everything* (except dark matter)

Though this may all seem very detached, keep in mind that these obscure particles are what comprise the atoms in our cells that make our body. So yes, the mass of the charm quark, and the human brain, and by induction the person reading this, is sourced by the Higgs mechanism.

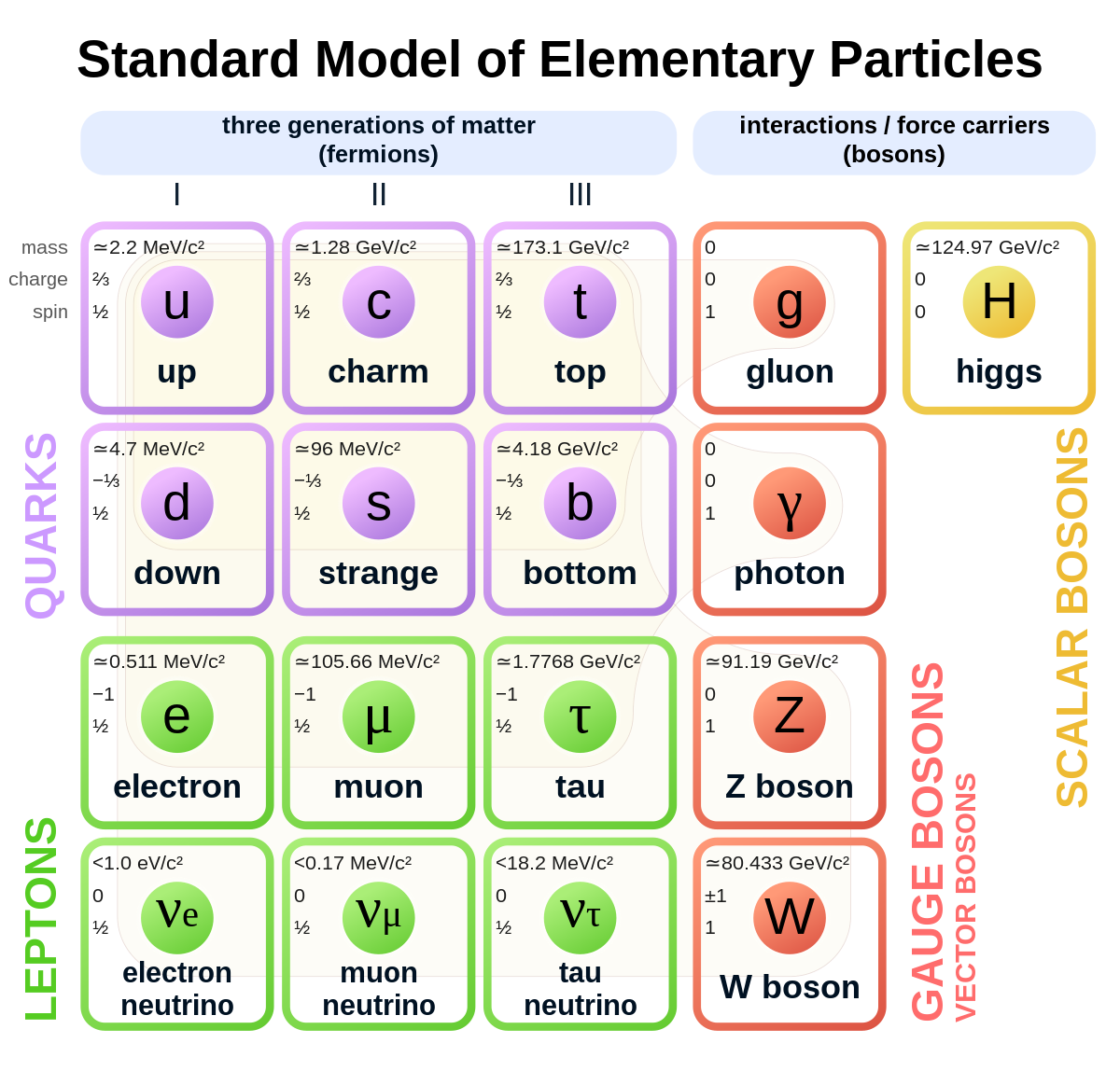

The anthropic principle is perhaps the most bold and controversial argument in high-energy theoretical physics and cosmology. There’s some interesting and necessary history here. In 1987, the renowned late physicist Steven Weinberg released a single-author paper titled “Anthropic Bound on the Cosmological Constant.” The cosmological constant is a candidate physical mechanism which would explain dark energy, the phenomena in which the Universe is expanding and accelerating in its expansion. In a much abridged version of the story behind this, Einstein manually added this term, $\Lambda$, in his field equations to enforce that the Universe be static; however, this was prior to Edwin Hubble’s observational evidence for the expansion of the Universe (Einstein, quite famously, was a big proponent of a static Universe. Even the greats are wrong sometimes). Einstein quickly abandoned his cosmological constant, but it wasn’t until much later in the late 1980’s that when the accelerated expansion of the Universe was discovered, that physicists re-embraced the cosmological constant for its ability to explain this “dark energy.” But if Einstein threw it away, and Einstein is certainly someone we trust and respect, is this a correct interpretation?

Einstein's brainchild featuring his 'biggest blunder.' But that pesky $\Lambda$ may be the solution to the dark energy problem.

The next natural question to ask, you may think, is the value of this constant. And if you are a philosopher, you may ask why that value is what it is. Weinberg argued that if $\Lambda$ was above a certain value, with all other physics staying the same, there would be no galaxy formation and by extension, no star and planet formation – and no life. This does not sound physics-y at all! In fact, it just sounds like some philosophical bullshit. But, if you think about it enough, it’s a valid, respected (though contested) argument to make on the matter. If the cosmological constant was sufficiently large that carbon-based life could not form, we would not be here to measure it.

I’ve been thinking about this argument a lot. I don’t necessarily know if I’ll adopt it, but I respect it. In a perfect world, I would like to abandon any and all thoughts that are concerned with numbers in physics. And no, this isn’t because I abhor the use of calculators and doing physics with anything but the Greek alphabet; it’s because these are hard questions! Johannes Kepler, of Kepler’s laws, was obsessed with the question of why the Earth-Sun distance is what it is – a number. We know now that this is not an interesting question at all! The more interesting question, which we can thank Newton for, is what mechanism is causing it to be what it is. If Kepler wondered about this, perhaps he would have discovered the laws of gravity before Newton.

There are a handful of numbers like this in modern theoretical physics that people obsess over. One such example is the fine structure constant, $\alpha$, which is the coupling constant for quantum electrodynamics. It enforces the strength of all interactions that have to do with electromagnetism. The fine structure constant is nearly 1/137, and the fact that it can be represented very accurately as a fraction is part of what makes it so elusive. There are quite a few important things that depend on this! For example, the reason the Hydrogen atom and others form and stay intact is because the fine structure constant allows it to be. What if it was different? Could atoms form? Would they form differently? Richard Feynman famously said “… all good theoretical physicists put this number up on their wall and worry about it.” Some even took this question to the grave:

- When I die, my first question to the devil will be: What is the meaning of the fine structure constant? - Wolfgang Pauli

Admittedly, from a physicist’s perspective, wondering about these things is both terrifying and arguably dangerous. I have not yet thought deeply about the fine structure constant.

But, I did wonder if the mass of the Higgs Boson could have been restricted via anthropic arguments. Of course, this question is no longer necessary, because as of 2012 we know what the mass of the Higgs is (~125 GeV), but for the sake of probing the strength of this argument more, I asked it. If the mass of the Higgs was different, and by extension the strength of the coupling of the Higgs field to matter, would everything be too massive? These differences are particularly important in the early Universe during Big Bang nucleosynthesis or inflation – when the apparent fine-tuning of the Universe really set the pace for the evolution of the Universe. My professor slightly scoffed and said he gave little thought to anthropic arguments. In fact, he retorted with suggesting that it should be more properly called anthropocentrism. Ever hear of geocentrism or heliocentrism? They’re extinct. Humans have rarely benefited from thinking they’re special.

The transition from geocentrism to heliocentrism was a huge paradigm shift in the history of science. This trend continued as scientists discovered our galaxy was not unique, nor our local galactic cluster. Continuing to scale up in size, the next argument would be that our Universe is not unique -- and this is indeed what string theorists believe (I do not study, nor intend to study (deeply) string theory).

In short, his stance is that the human experience is not preferential in the grand scheme of the cosmos. That the fact that we are here to theorize and measure properties of the Universe does not mean that the Universe was catered for the prescription of physical constants that yields the physically realizable configurations that allow us to exist. Sorry for the wordiness, but I want to emphasize that I don’t think the anthropic argument is necessarily preferential to the human experience, but for the physics that allows mankind on Earth to exist in the first place. There is a difference.

Physicists are not only concerned with phenomenology but methodology. Are we conducting science in the most efficient / correct way? Are we even pursuing the right questions? That is the most difficult question of all.