A Brief Aside on Mathematics

Published:

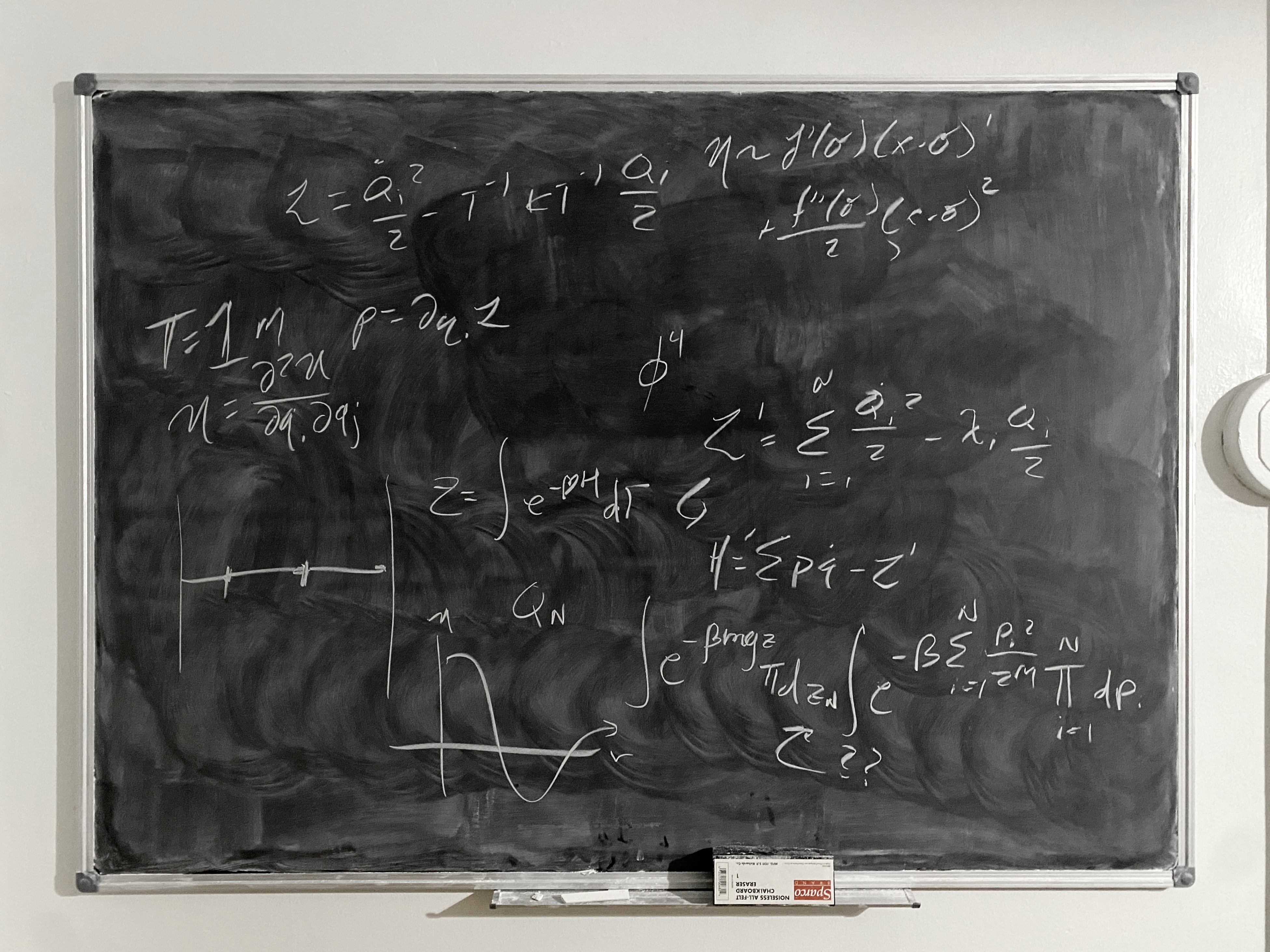

Math is one of the non-negotiables of being a physicist. I do math a lot, every day. It is as natural for a physicist to do math as writing is for an author. But I’ve recently took some time to reflect on the math I know and do so frequently, and when math transitioned for me as just another subject in school to something profoundly important and necessary. One day I was doing multiplication tables, the next I was considering infinite dimesional vector spaces in Quantum Mechanics. How the fuck does that happen?

"A recent Amazon giftcard impulse-buy for my apartment. "

It has certainly had a toll on my ego. The more math I learn the less I know. It’s like playing a game with an infinite skill cap. Math is also unforgivable. A missing factor of two or displaced minus sign could ruin your entire day. Yet somehow, I still keep doing it.

I never had a vendetta towards math growing up. I didn’t particularly enjoy it, but then again math didn’t start being even vaguely interesting until calculus, which was introduced to me in the 12th grade. My position on math as a whole solidified as I was introduced to more complex mathematics for physics; then it became clear to me that math is not only a method, but a language and a form of expression. For some reason or another, Nature has chosen math as the avenue to reveal Her secrets.

And it is not intuitive for this to be true! Life is biological, its processes’ are chemical, and the atoms are governed by physics. Yet, there is math beneath it all and this sentiment has been discovered and rediscovered by mathematicians and physicists alike for thousands of years. Pythagoreans (followers of Pythagoras) held the doctrine, “Numbers rule the world,” following the footsteps of their teacher who built on many important ideas from Euclid. Much Later, Galileo famously wrote that “The book of nature is written in the language of mathematics.” The math that so many of us take for granted actually provided humanity the first glimpses into Nature, and were quintissential in the development of the sciences, economics, and countless other disciplines. The development of the modern world is a testemant to the role math has had and will continue to have, whether we like it or not.

But now we have computers, and iPhones, and AI, and Amazon x Whole Foods. Is there any point in learning all this old math and is it worth looking for more? Is research in pure mathematics worth funding?

(yes)

Math, in fact, continues to be the cool new kid on the block. Without getting into excruciating detail, any and all blockchains are products of fundamental mathematics. Zero-knowledge proofs, developed in the 1980’s, are an avenue for powerful encryption schemes being used in some cryptocurrencies, and the global crypto market size in 2020 was valued at $1,500,000,000.00. Artificial intelligence (AI) also benefits from math. Neural networks were first developed around the late 1950s, inspired by the structure of biological neurons. Their inner machinery is surface-level just a bunch of matrix multiplication, one of the first things learned in an introductory linear algebra course. Their success as a whole, however, still remains largely elusive (think: how do we go from billions of water droplets to waves?). In the past few years, an exciting equivalence has emerged between kernel machines, a much older idea in mathematics, and neural networks. Needless to say, there is money in AI. And by extension, there is merit in learning and pursuing mathematics, old and new.

I think its a significant failure of the American education system to emphasize meaningless arithmetic for most students’ math education, and I believe the way the math curriculum is currently structured is the fundamental reason why so many adults despise math and believe they are bad at it. Knowing what 8x7 is at best convenient, and understanding fractions and percentages is nice when figuring out how much to tip your bartender. But doing it fast is irrelevant because our phones can do all that – and much more – much faster than us. It’s dissapointing to think that so many peoples’ perceptions of mathematics is tainted by procedural arithmetic like this.

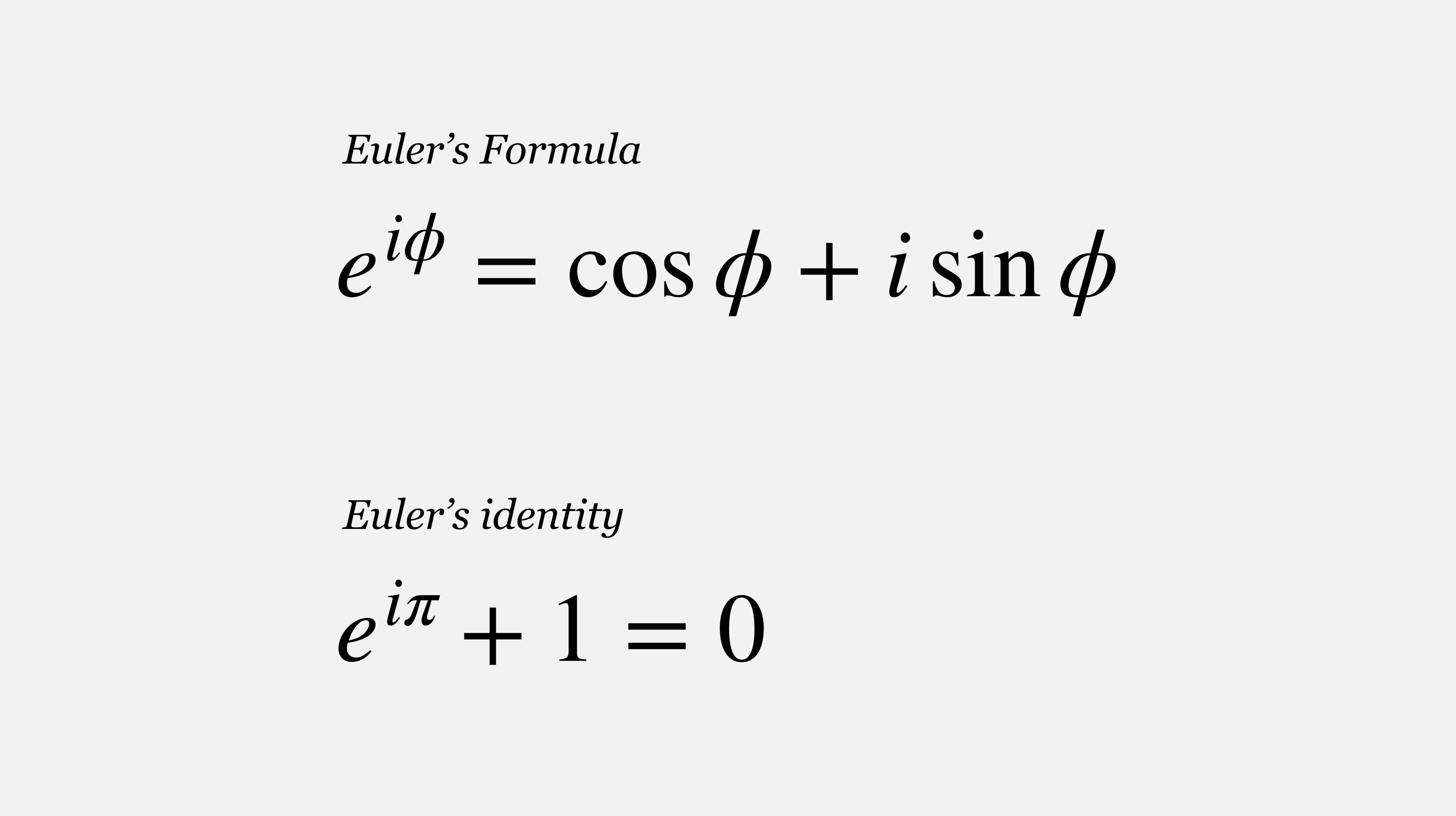

Even in high school when transitioning towards more complex mathematics, math was still taught under the guise of being something methodic that required useless, useless memorization. The emphasis was put on learning a well-defined procedure rather than developing mathematical intuition, and there was hardly any mention of the bigger picture at hand. When learning trigonometry, are we told how the unit circle is actually the language of waves, and how Louis de Broglie discovered in 1924 that all matter has an associated wavelength, so certainly there is some importance in this idea? Do we learn that the number e is simultaneously the language of compound interest, population growth, and the bridge between the real and complex numbers? Were we taught that the existence of pi provides immense insight into the geometry of our Universe? Or were we taught that pi is just

3.1415926535897932384626433832795028841971693993751058209749…

None of this was deemed that important, but doing long division by hand was.

"Perhaps the most beautiful and famous equation in all of mathematics."

There is prose in mathematics; proving things requires rhetoric and so does approximating things (I shamelessly do the latter much, much more than the former). I do not know how to do long division by hand and I sometimes plug 8x7 into my calculator. And I certainly dont know how to integrate by hand, anymore. Yet I call myself a “math person.” This goes to show that math is something inherently much deeper than the distorted perceptions of method and arithmetic many may have. Mathematics = language = art = nature = ∞-ly much more.