Promises Unkept and the Promise of Rubin

Published:

It’s been jarring to watch public trust in science deteriorate so rapidly since I began my career in academia. Maybe it started with vaccine misinformation in the early 2000s. Or maybe it was the growing politicization of climate change throughout the 2010s. Or maybe what really did it was COVID, when doctors—often in vain—pleaded with people to mask up and keep their distance to slow the pandemic. And now we’ve arrived at a moment where the Trump administration has made a firm financial statement that, in theory, reflects the electorate’s perception of science. A part of me still hopes that isn’t true.

It has been the blessing of a lifetime to learn about Nature and Her secrets for the past eight years. In that time, I’ve learned to delineate between the promise of science and science in practice. While I still respect the beautiful beast that is academia, my time with it is likely waning. That realization is hard, and for an astrophysicist and cosmologist like myself, the timing could not be worse.

I first learned about the Vera Rubin Observatory, then called the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, in 2019. Most of my work — in both undergrad and grad school — has been in preparation for Rubin. To date, I’ve written eight papers; five mention the observatory by name, including my very first paper in 2020. At a Rubin Observatory “first images” launch event, a professor on the panel flashed a slide of his own first paper, written in the 2000s. The Vera Rubin Observatory was also mentioned.

"The Vera Rubin Observatory on the of summit of Cerro Pachón in Chile."

Image credit: The Vera Rubin Observatory

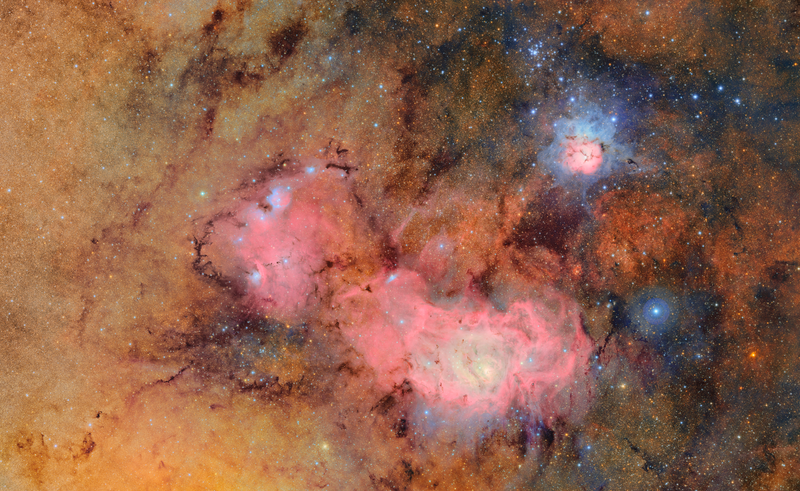

Rubin is a game changer. It will collect 20 terabytes of data every night for 10 years. The last survey of this kind was the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), which was operational in its bulk from 2000-2008, and collected 200 gigabytes of data every night. SDSS revolutionized astronomy by mapping a third of the sky and cataloging millions of galaxies, but Rubin will do this every few nights, with far greater resolution and cadence. It’s estimated to observe 20 billion galaxies over its 10 year survey. Whereas SDSS gave us a snapshot of the Universe, Rubin will give us a movie. There’s a reason Rubin has been appearing in papers for nearly two decades before it even began collecting data.

"The Trifid and Lagoon Nebulae imaged by Rubin."

Image credit: The Vera Rubin Observatory

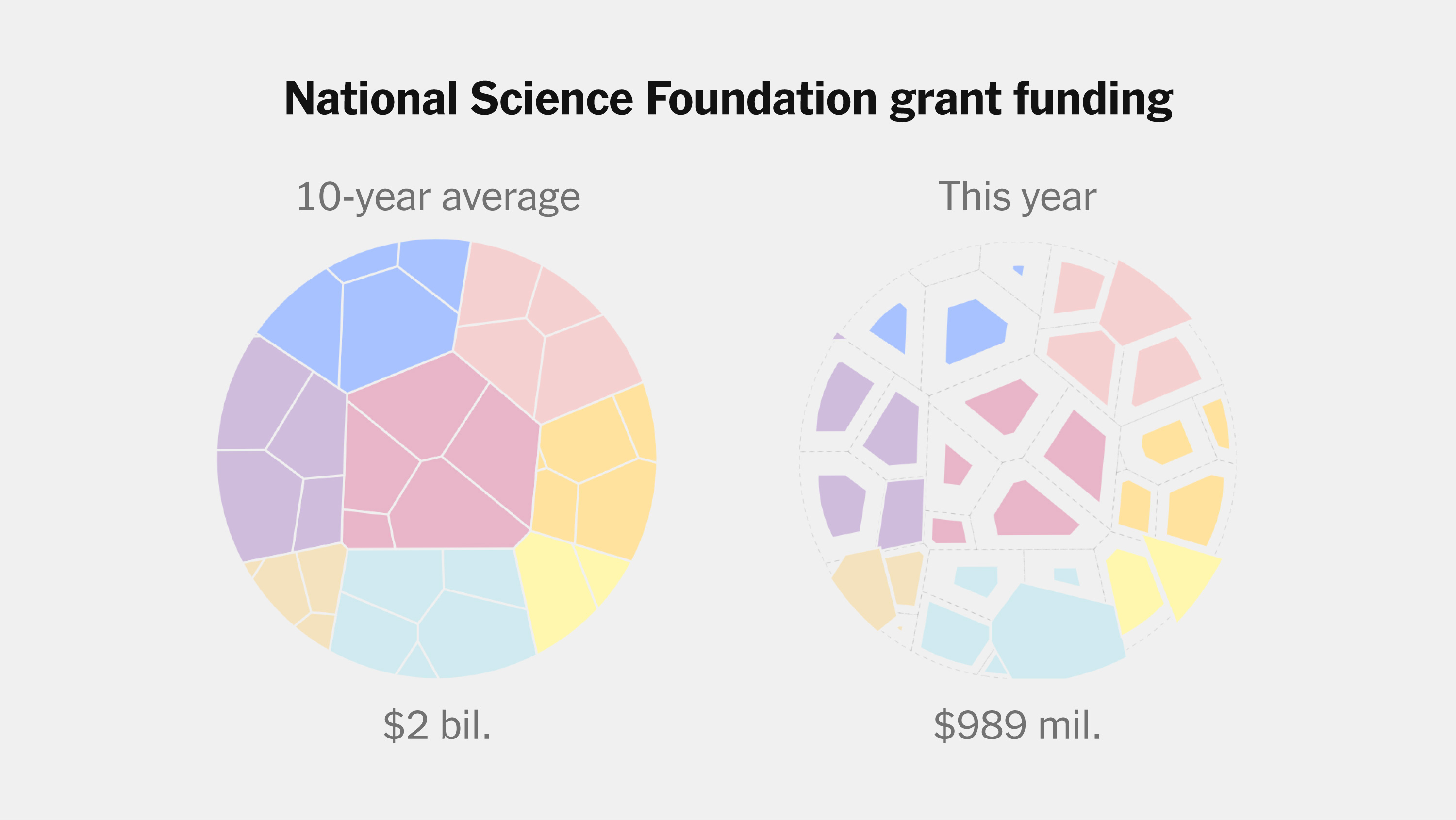

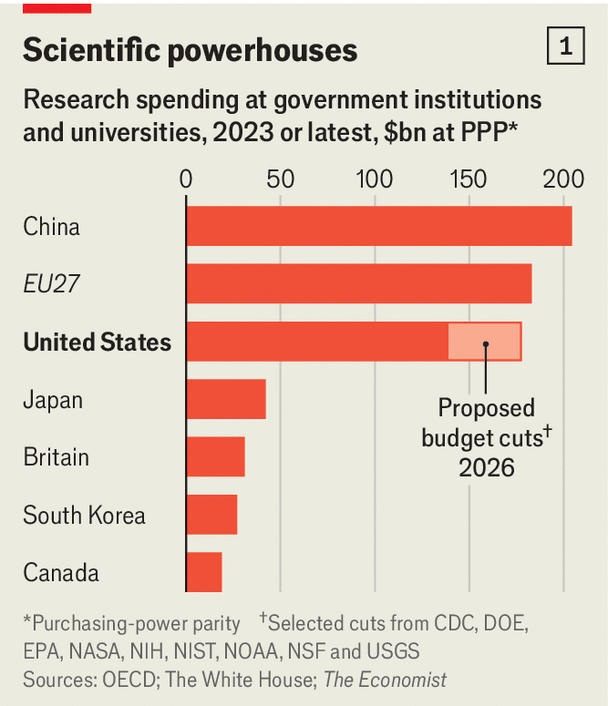

So much of the community has spent so long preparing for this moment, and it’s bitterly ironic that just as Rubin’s journey begins, a wave of politically charged, largely baseless skepticism toward science is crashing through Congress. This is nothing new, of course, but it seems that this administration is not simply baring its teeth, as per the FY2026 proposed budget. This has real implications for what Rubin can achieve during its 10 year survey. In fact, it is changing what scientists (including myself) can achieve right now.

A professor in my group at Northeastern specializes in dark matter searches using balloon-borne telescopes. These are a low-cost alternative to space-based observatories. They fly high enough to block out most atmospheric distortion and can collect high-quality data at cadences similar to space telescopes, but at a fraction of the cost. For comparison, the James Webb Space Telescope cost over $10 billion. A project like SuperBIT, which launched a balloon-borne telescope into the stratosphere, came in at under $10 million. That is <0.01% the cost of JWST, and yet, the FY2026 proposed budget for NASA completely eliminates its balloon program. Read that last sentence again.

- “…but if this budget passes as proposed, it’s going to be catastrophic for the ability of this group to do its research.” - Northeastern University Professor, 2025.

Ok, but Rubin is much more expensive and also an international effort; the NSF cannot get the money back already spent on the telescope. Even then, it wouldn’t be in their interest to completely eliminate US participation in the telescope’s science after such a large investment. Though this may be the case, the impact (or lack thereof) on Rubin science from the USA may be drastic.

Most of the analyses that drive science — especially in large collaborations like Rubin — are done by graduate students. We are the cheap, skilled labor force that props up academic research. But universities have been under siege from Trump-era attacks on higher education. As a result, many graduate programs have either stalled admissions or drastically cut the number of students they accept. That means fewer people to analyze Rubin data.

"Visualization of the proposed ~$5 billion cut to the National Science Foundation, the largest funder of basic science in the US."

Image credit: The New York Times

Many of my friends are also international students. Roughly 33% of STEM graduate students in the United States are visa holders. 50% of postdoctoral associates are. It is already immensely difficult to be an underpaid and overworked graduate student; I could not imagine the added pressure of being so far from my family and friends. The Trump administration has begun weaponizing visas and ostracizing international graduate students, most recently (and infamously) attempting to revoke Harvard’s ability to sponsor graduate student visas. I have friends that are graduate students at Harvard, some of whom work on Rubin. It’s uncertain whether anything will actually come of this, but it’s valid to experience job insecurity when the most powerful man in the world is threatening it. Fewer people to analyze Rubin data.

On top of that, faculty apply for research grants to fund the very science they propose — funding that depends on there being people (read: grad students and postdocs) to actually do the work. Many of those grants are being slashed. These are the same grants that universities take a sizable cut of to fund broader institutional needs. One of those needs is teaching assistants (TAs): so fewer grants means less institutional funding, which means fewer TA positions. That, in turn, makes it harder to support new grad students. The cycle is vicious, and it’s disheartening. I recognize that scientific progress frequently seems very detached from the human experience. But keep in mind that it is people doing this, at the end of the day.

"The nation that out-educates us today is going to out-compete us tomorrow." - Barack Obama, 2009.

Image credit: The Economist

As I near the end of my degree, I didn’t plan for my potential exit from science to coincide with the most extraordinary influx of astrophysical data we’ve ever seen (Rubin has been delayed quite a bit). I also didn’t plan for it to align with a looming brain drain in academia — not due to lack of talent, but from deliberate and growing ostracization by the public and by our own government. There are a few postdoc positions that I would love to land; it’s unclear if these positions will be offered this next cycle, or whether they will be funded for the duration as promised. It’s again a lack of job security, put simply.

I’m excited for what’s to come. I truly am. But I write this as a kind of apology — to my younger self. The one who believed this — that is, science in an academic setting — was their life’s calling. The one who thought science was something to be celebrated across political lines: that funding science was synonymous with investing in the welfare of society. The latter, of course, I still think is true. What I’m sorry for is that I have to defend it.

I have spent much of my time thinking about things that are up, but reality grounds you, at the end of the day.

"The Hubble Deep Field (HDF) was one of the first images that inspired me to further pursue astrophysics and cosmology. Pictured above is "Cosmic Abundance" by the Vera Rubin Observatory. It looks a lot like the Hubble Deep field image, except that image was taken from space and this one from Earth. HDF was imaged over days and this image over minutes. This image from Rubin also covers a portion of sky over a hundred times that of the Hubble Deep Field.

Image credit: The Vera Rubin Observatory

The light of Rubin had already inspired thousands long before the observatory found its home in the mountains of Chile. It inspired me — back when I was a college student, in awe of Nature and unaware of the political machinery that enables (?) the pursuit of science. The light of Rubin is now here. I will keep celebrating the Vera Rubin Observatory — whether I remain in academia or not. Not because the system makes it easy, but because it is what I have always done. It’s just that at this moment, I consider that celebration also an act of protest.